This bibliography covers a renaissance of Ockham scholarship during a seventeen-year period in the middle of the 20th century, mostly works in English, French, and German.Access-restricted-item true Addeddate 01:38:23 Bookplateleaf 0004 Boxid IA40081921 Camera Sony Alpha-A6300 (Control) Col_number COL-658 Collection_set printdisabled External-identifier This bibliography covers the majority of the first half of the 20th century, mostly works in English, French, and German. This bibliography covers the majority of the 20th century, mostly works in English, French, and German.

In chronological order, the first is Heynick 1950, then Reilly 1968, and last Beckmann 1992.īeckmann, Jan P. At the same time, however, he upheld the absolute omnipotence of God, which committed him to “divine command theory” in ethics-God can command individuals to do things that may ordinarily be wrong (such as disobey the pope), making them right through his command.īibliographies of the Secondary LiteratureĪ few bibliographies of works about Ockham cover most of the 20th-century scholarship. Against the scholastic mainstream, he insisted that theology is not a science and rejected all the alleged proofs of the existence of God. Throughout his career, Ockham remained a fideist, convinced that belief in God is a matter of faith alone. He never returned to finish his degree (hence his nickname, “Venerable Inceptor”) but, from exile in Germany, wrote political treatises that provide groundbreaking defense of individual rights, separation of church and state, and freedom of speech. After four years under house arrest, he escaped, claiming Pope John XXII was a heretic himself. Though Ockham’s dispute with church authority began with metaphysics, it soon became political. Consequently, he was summoned to the papal court in Avignon before he was able to finish his degree at Oxford University. Ockham’s ontological reduction was suspected of having unorthodox implications for the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, according to which bread and wine is miraculously transformed into the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

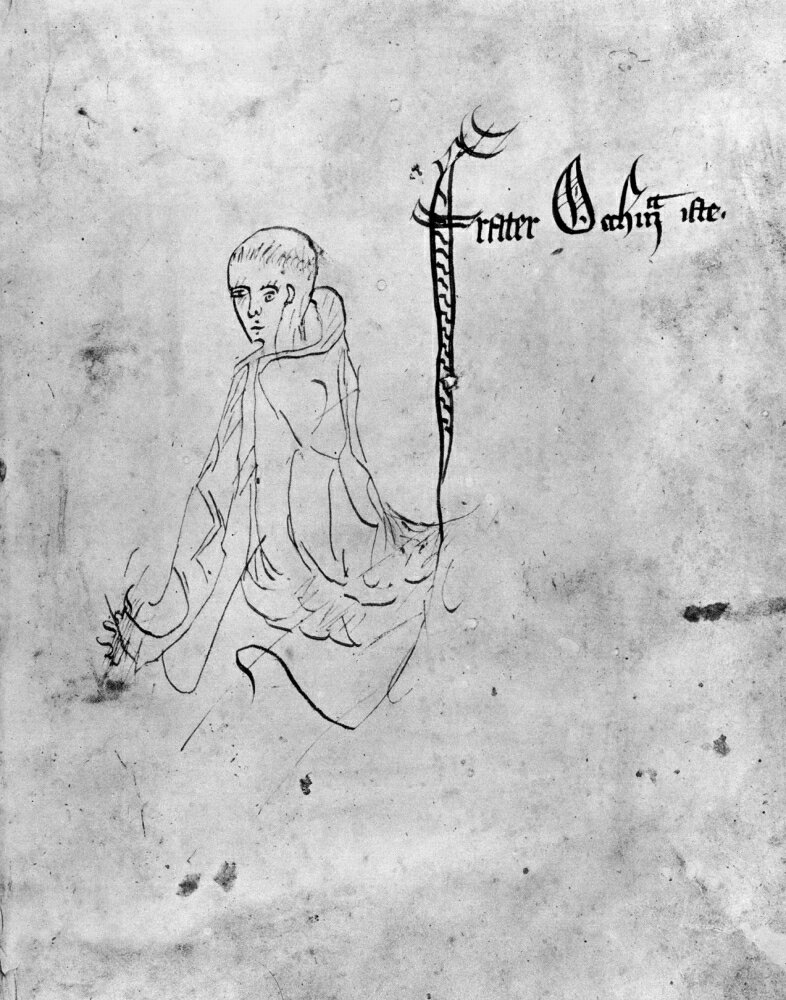

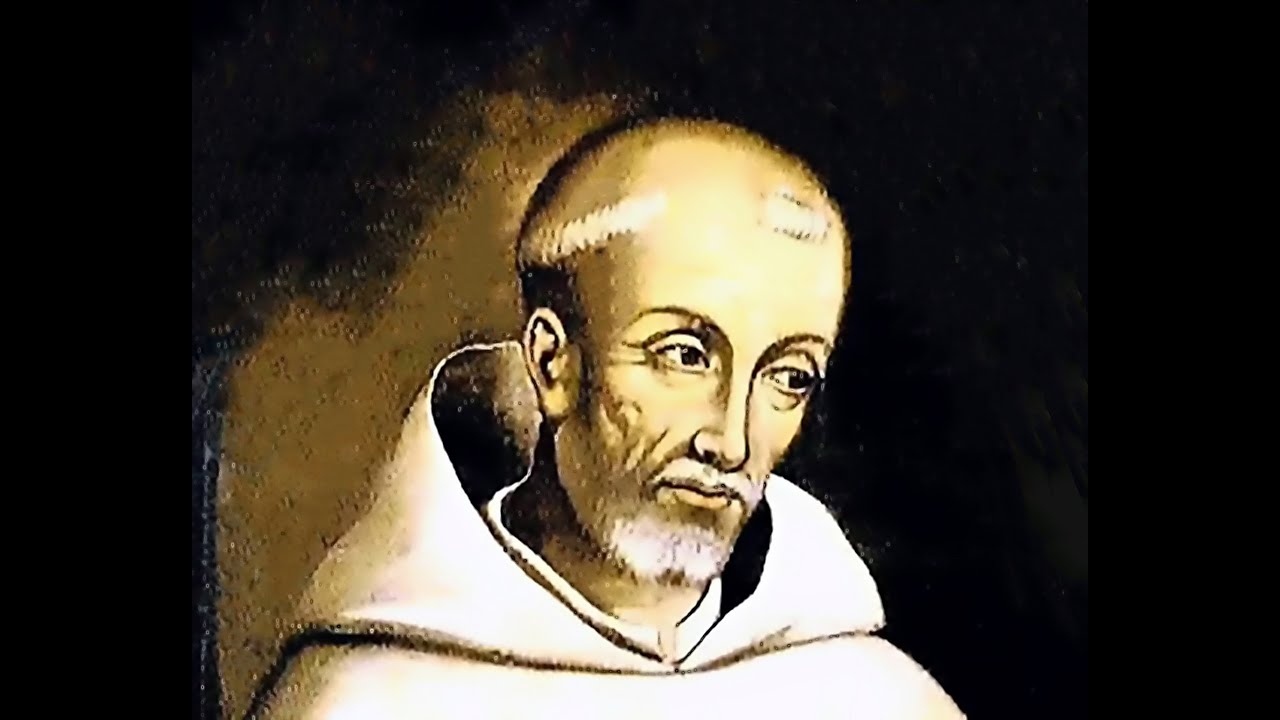

For example, the universal term “man” refers to this or that man while grouping them with all the other men. His theory of mental language aimed to show how we can speak of universals without thereby presupposing that universals exist. He contended that human beings perceive objects directly through “intuitive cognition,” without the help of any universals. This helped him to advance a new version of nominalism, according to which universals, such as man, are not metaphysical realities but only concepts in the mind. Above all, Ockham used the Razor to interpret Aristotle in a more radically empiricist manner than did his predecessors, accepting into his ontology only individual substances and individual qualities. Although Ockham did not invent the Razor, he wielded it so systematically and with such striking effect that it came to bear his name. His claim to fame was “Ockham’s Razor,” the principle of parsimony, according to which plurality should not be posited without necessity. William of Ockham ( c. 1285/7– c. 1347) was an English Franciscan philosopher who challenged scholasticism and the papacy, thereby hastening the end of the medieval period.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)